Floating wind turbines: new horizons for offshore wind turbines

Installing wind turbines far from the coasts to catch the regular power of offshore winds and resolve the constraints due to the depth of the sea bed... this is the definition of “floating” offshore wind turbines. R&D has been involved since 2011. A solution for the future which will contribute greatly to the energy transition Objective: support the development of EDF power solutions projects and contribute to the emergence of the sector

Offshore wind turbines: a strong link in the energy transition

Wind turbines are already turning at sea, and all eyes are on this sector. In the context of the energy transition, offshore wind turbines have many assets to offer. While it operates in the same way as onshore wind power - capturing the wind's energy and converting it into electricity - it benefits from more regular and more intense offshore winds. As a result, floating wind turbines are even more efficient, while their location at sea limits the noise and visual pollution that are more dreaded on land.

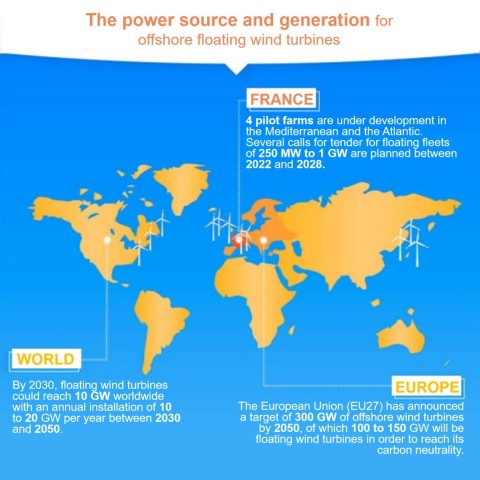

In fact, the offshore wind market is growing exponentially all over the world, with Europe leading the way. And with excellent reason: to achieve the hoped-for carbon neutrality by 2050, the European Union has pledged to support the development of the industry. The aim is to increase Europe's offshore wind generation capacity from the current 12 GW to at least 60 GW by 2030 and 300 GW by 2050. That's 25% of its electricity production. As part of its Multi-Annual Energy Programme (PPE), France is aiming for installed offshore wind power capacity of 2.4 GW in 2023 and around 5 GW in 2028. This capacity includes a proportion of floating wind power, which is set to increase from 2028 onwards.

Floating wind turbines: new perspectives

Floating wind turbines will allow access to areas where fixed offshore wind turbines cannot go. A “fixed” wind turbine involves installing the foundations of a wind turbine on the seabed, at a depth of between 50 and 60 metres. This is why they have mainly proliferated in shallow marine areas, such as those of the North Sea... A floating wind turbine is free from this depth constraint. Its design principle? The wind turbine (turbine, mast and blades) is mounted on a floating foundation, the whole unit is constructed and assembled in port, then towed to its operating location before being tied to the seabed with anchoring lines.

Compared to classic solutions, the floating wind turbine allows projects to be installed in areas of great depth, further from the coast or with more wind. The majority of floating projects constructed or under construction are in less than 200m of water, but much deeper sites are being studied. In doing so, it multiplies the potential of offshore wind turbines. In order to take advantage of these favourable conditions on a large scale, a number of obstacles still need to be overcome. The field of possibilities is vast... the limit is in our ability to bring the energy ashore and to install and exploit infrastructures the size of the Eiffel Tower, at several dozen kilometres from the coast.

A technical challenge in movement

Objective: taking the leap forward to large scale industrialisation. R&D has been working on this for several years, in support of various projects carried out by EDF Renewables in France. Among them: Provence Grand Large (PGL), a pilot industrial park, unique in the world. With 3 floating wind turbines of 8 MW in the Mediterranean, it is expected to be commissioned in 2022. Our programme consists mainly of “de-risking” this technology. Making a wind turbine float remains a challenge, as factors causing instability are numerous: movement of the blades and the sea, height and weight of the turbine. It is a question of choosing the right float and we are studying several technologies using a tool that models the wind turbine in operation which allows us to test the different alternatives in the least favourable conditions. The environment is also one of the key subjects of R&D in this field: impact on the seabed and on birdlife, consequences of bio-fouling (formation of a troublesome layer of living organisms on the surface of the float) on the weight and therefore the equilibrium of the floats. In the longer term, R&D also predicts problems linked to their maintenance and ageing.

Pooled research

In France, seven offshore wind turbine projects planned by the PPE are under development, and calls for tenders for floating wind turbines are increasing. Faced with the drastic drop in the number of onshore, solar and fixed wind turbines, the floating wind turbine has a challenge to survive in order to stay in the race... And in this context, EDF's ambition is to gain a significant market share. But beyond the commercial issues, it is a question of helping the sector to gain in maturity by pooling expertise, so that energy companies and the entire value chain of suppliers and service providers have the ability to learn about floating wind turbines. EDF has therefore joined forces with France Energie Marine, a research institute dedicated to marine renewable energy. Created in 2012, this purpose of this ITE is to consolidate French academic and industrial research into the development of offshore wind turbines.

R&D and floating offshore wind power

Duration: 1:29

Your browser does not support javascript.

To enable you to access the information, we suggest you view the video in a new tab.

R&D and floating offshore wind power

Floating offshore wind is an extremely high-potential renewable energy.

This emerging technology allows wind turbines to be installed further from the coast at depths exceeding 50m where winds are stronger and more stable.

To support its development, EDF's R&D department is focusing its work on de-risking the technology and reducing production costs.

In particular:

- Selecting the floats and mooring systems, adapted to each installation thanks to digital simulation supplemented by tests with reduced-sized models in a testing basin.

- Optimisation of marine operations, for the construction and maintenance of wind farms.

- Accurate assessment of the generating potential.

- Electrical connection solutions for wind farms.

- And systems to improve the carbon assessment.

One of the flagship projects is "Provence Grand Large". The concept: install three 8-megawatt floating wind turbines, each off the Mediterranean coast.

The R&D department has supported EDF Renewables in modelling, designing and selecting the floats: a world first with this type of float.

Many projects are currently underway involving other types of floats and the R&D department is proud to be providing its expertise.

More information on edf.fr/en/research

Ports: strategic design platforms

The port infrastructures will play a very important role in the development of floating wind turbines. The reception and construction site for wind turbines, they must acquire the ad hoc logistical skills to manage not only the series construction of floats and wind turbines, but also the stock of materials for fleets of up to 100 wind turbines. A crucial issue which affects the regions.

Digital technology for floating offshore wind power

Modelling, calculation chains, digital twins, and also artificial intelligence... digital technology is at the heart of research on floating offshore wind turbines, whether for the design of the float, the understanding of the mechanisms involved, monitoring or maintenance... An update from Christophe Peyrard, expert research engineer in the LNHE* department at EDF R&D, in charge of digital simulation on floating wind turbine foundations.

How were you brought in to work on floating offshore wind turbines at EDF

Floating offshore wind power is a new technology that is bringing with it a whole host of players: float developers, turbine manufacturers, etc. The first prototypes were developed in Norway in 2009, followed by Portugal, Japan and France. EDF power solutions has rapidly positioned itself in this market, with a project to install 3 floating wind turbines off the coast of Marseille due to come on stream in 2022. In the meantime, digital simulation is proving to be faster and more cost-effective than prototype tests or tank trials. Our role at the R&D is to guide the operational entities in their choice of the best technologies, in terms of both performance and cost.

What are the specific features of this technology in terms of numerical simulation?

Floating offshore wind energy is at the crossroads of two industries: the electricity industry (using wind energy), where we study a machine that turns on a wind turbine mast, and the offshore oil industry, which models systems that move in the waves. From a numerical point of view, we therefore need to combine the two types of model to ensure that the system can withstand the stresses that will be applied to it. To do this, R&D has developed a calculation chain called DIEGO, which enables us to check a number of points, such as the stability of the system (depending on the design of the float and the weight of the turbine, we can ensure that the whole thing won't tip over), its dynamic behaviour in waves, its structural design and its resistance to extreme conditions (storms), as well as its resistance over time to repeated micro-stress (fatigue calculation). In this way, we can compare the different float technologies available on the market.

How did you go about it?

We started working on floating wind turbines at R&D in 2011. At that time, the idea was to install wind turbines with a vertical axis, unlike traditional onshore wind turbines, which have a horizontal axis. On paper, the vertical axis offered a number of advantages for floating wind turbines, as it allowed us to use smaller floats and was better able to withstand tilting. When EDF power solutions brought us on board for this project, there was no tool for modelling this type of wind turbine on a float. So we built a computing core that gradually evolved into a complete floating wind turbine simulator. After six years, this technology was abandoned in favour of horizontal axis wind turbines for reasons of cost and industrial maturity. We had to rework the code... but we now have a tool that enables us to process any type of wind turbine. We are currently working on making it easier to use for the engineering units. This involves a more accessible and practical interface. A development that requires an iterative approach with users.

What are the next steps?

As well as making the tool easier to use, we need to better identify its limitations... so that we can optimise it. At the moment, because of the very large number of criteria to be taken into account (wind direction, wind speed, gusts of wind; the same goes for waves: their direction, their height, marine currents, the tide, etc.) we are working on simplified models so that the calculation chain can run fairly quickly. We now need to compare it with more precise tools to assess the degree of uncertainty, and when this is too great on certain points, propose improvements that are still simple and fast. It's a process of continuous improvement, which can sometimes lead us to considerably rework what has been done so far. In the medium term, the Diego calculation chain will also be used to develop a digital twin, a sort of digital replica of a physical floating wind turbine, which could be used to optimise the maintenance of the assembly, or to find design margins to reduce costs. In the longer term, we also plan to use artificial intelligence to analyse the data from the prototypes that will be installed off Marseille as part of the Provence Grand Large project. Our approach via the Diego chain is to study the system using our knowledge. Artificial intelligence, on the other hand, can be used to learn from experience in a more heuristic approach, by ordering all the data obtained from observation in the field (for example, if a problem occurs every six hours, I deduce that it may be linked to the tide). Two highly complementary approaches, which demonstrate the contribution that digital tools can make to meeting the challenges of the energy transition!

*LNHE: National Hydraulics and Environment Laboratory

From overhead lines to floating offshore wind, and tidal power...

Itinerary of an enthusiast for fluid-structure interactions

With his engineering degree from the Ecole des Ponts et Chaussées in his pocket, Christophe Peyrard carried out his end-of-study placement at EDF R&D, attracted as much by the technical problems addressed as by the quality of the researchers he was to work with. In 2005, following his placement he joined the THEMIS department, which has now become ERMES, to work on overhead lines, more specifically on the strength of electrical pylons and cable vibrations.

When wind turbines started to be developed, he became interested in fluid-structure interactions: at first wind, then waves... which led him to join the teams at the National Hydraulics and Environmental Laboratory (LNHE) in 2011. He worked on tidal power, a technology which involves using marine currents to produce electricity, Then he became interested in wave models for the protection of EDF’s coastal installations, thus cultivating his appetite to study hydrodynamic forces applied to structures In 2012, he turned his attention to floating wind turbines. “We didn't really know what it was going to be like at the beginning and there weren't many of us working on it, we didn't have a lot of time set aside for it... Then from 2015, the project started to grow. It now occupies 100% of my time and employs the equivalent of three other people in R&D”

As leader of the activity on floating bases, his job today is to coordinate studies on the subject according to the in-house requirements. “This has given me a wider view of the subject, which covers not only technical aspects but also the industrial context and economic issues. You have to keep up to date with the latest technologies, know the actors, to provide as much information as possible to operational entities in order to help them identify the best technologies”.

His motivation? There are two sides: “Renewable energies are set to take more and more of a role in the context of the energy transition, It is motivating to say that you contribute in your small way to climate issues But the challenge is also technical: the phenomena involved in a floating wind turbine are very complex and touch on several fields in physics This multi-disciplinary approach encourages team work, and is exciting! Not to mention the digital modelling aspect, a very innovative field in which you learn something every day and where everything has yet to be built!”